Using bridge networks for simple and secure inter-container communications

Docker is a very convenient tool to deploy your applications to any machine with almost no effort. However, it does has some quirks that beginners tend to miss that can cause serious security issues, especially related to networking. In this post, I will cover a bit on what it means to expose container ports using Docker, why you shouldn't do it unless you absolutely have to, and how to use bridge networks instead.

The convenience of Docker

Docker is a technology that simplifies deployments on any machine. It allows developers to bake their application's setup and install process into images by writing them into a Dockerfile. Afterwards, you can build a Docker image

based off the Dockerfile and upload the image into a container registry.

FROM node:18.20-bullseye-slim AS builder

WORKDIR /app

COPY package.json package-lock.json nest-cli.json tsconfig.json tsconfig.build.json ./

COPY prisma ./prisma

RUN npm ci

RUN npx prisma generate

USER node

FROM node:18.20-bullseye-slim AS prod-builder

WORKDIR /app

COPY \

/app/package.json /app/package-lock.json /app/nest-cli.json \

/app/tsconfig.json /app/tsconfig.build.json ./

COPY /app/node_modules ./node_modules

COPY /app/prisma ./prisma

COPY src ./src

# Run the build command which creates the production bundle

RUN npm run build

ENV NODE_ENV=production

# Running `npm ci` removes the existing node_modules directory and passing in --only=production ensures that only the production dependencies are installed. This ensures that the node_modules directory is as optimized as possible

RUN npm ci --omit=dev && npm cache clean --force

RUN npx prisma generate

USER node

FROM node:18.20-bullseye-slim AS runner

RUN apt update && apt install -y wget && rm -rf /var/lib/apt/lists/*

WORKDIR /app

ENV NODE_ENV=production

ENV APP_PORT=8080

# Copy the bundled code from the build stage to the production image

COPY /app/node_modules ./node_modules

COPY /app/dist ./dist

EXPOSE 8080

HEALTHCHECK \

CMD wget --spider http://localhost:${APP_PORT}/api || exit 1

CMD ["node", "dist/src/main.js"]

All you have to do to run your app on any machine is to just have Docker installed on it and you can just pull

the image you uploaded to the registry and run it as a Docker container. The following is an example of how to run a Docker container called app-backend-prod using the latest version of an image called app-backend pushed by a user named chevonair. You can add runtime configuration through environment variables or through a .env file.

docker run --name app-backend-prod --env-file .env -p 3000:8080 -d chevonair/app-backend:latest

To avoid repetitiveness, you can configure a docker-compose.yml file which serves as a template that the Docker

Compose program can use to run the containers.

services:

backend:

name: app-backend-prod

image: chevonair/app-backend:latest

env_file: .env

ports:

- 3000:8080

Connecting to a Docker container

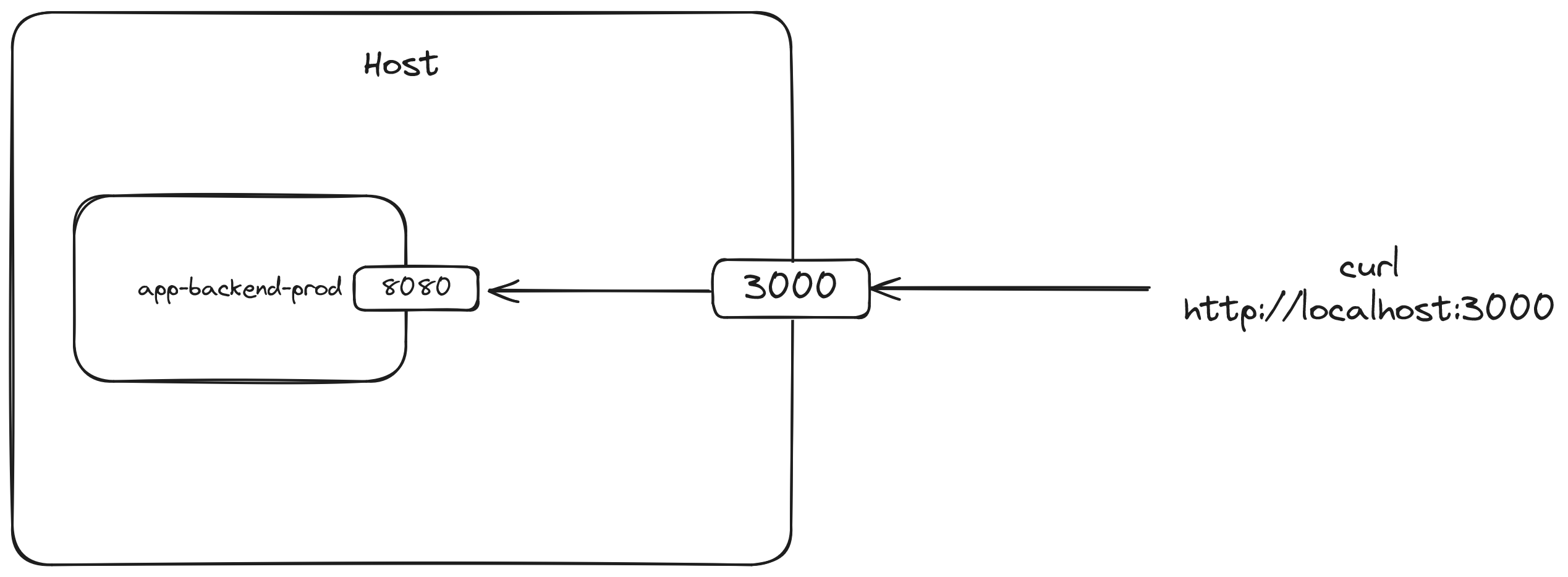

We can see that the ports directive of the docker-compose.yml file is a list of values. The values are mappings between a port on the host to a port on the container which is written as <host-port>:<container-port>. The example above means we want to direct any traffic on the host to port 3000 into port 8000 of the container.

If we don't specify a mapping, we won't be able to access the container from the outside world, even on our own machine where it's running. This is the expected behavior: the concept of Docker containers is that they have their own environments and runtime, almost like a mini-virtual machine. They also have their own network and ports separate from the host. So we have to expose the port of a container and map it into the host if we want to access it through the host. In this setup, the app is running inside of the container on port 8080. Assuming that this is running on our local machine, if we want to access the app through our machine AKA the host, we could open it on http://localhost:3000.

Aside from deployments, Docker is often used to setup dependencies for local development such as databases, in-memory datastores, other services, etc.

The risk of exposing ports blindly

Exposing ports on a local machine is fine but for production deployments, you don't want to risk opening ports where you don't need to as it expands the attack surface of the machine.

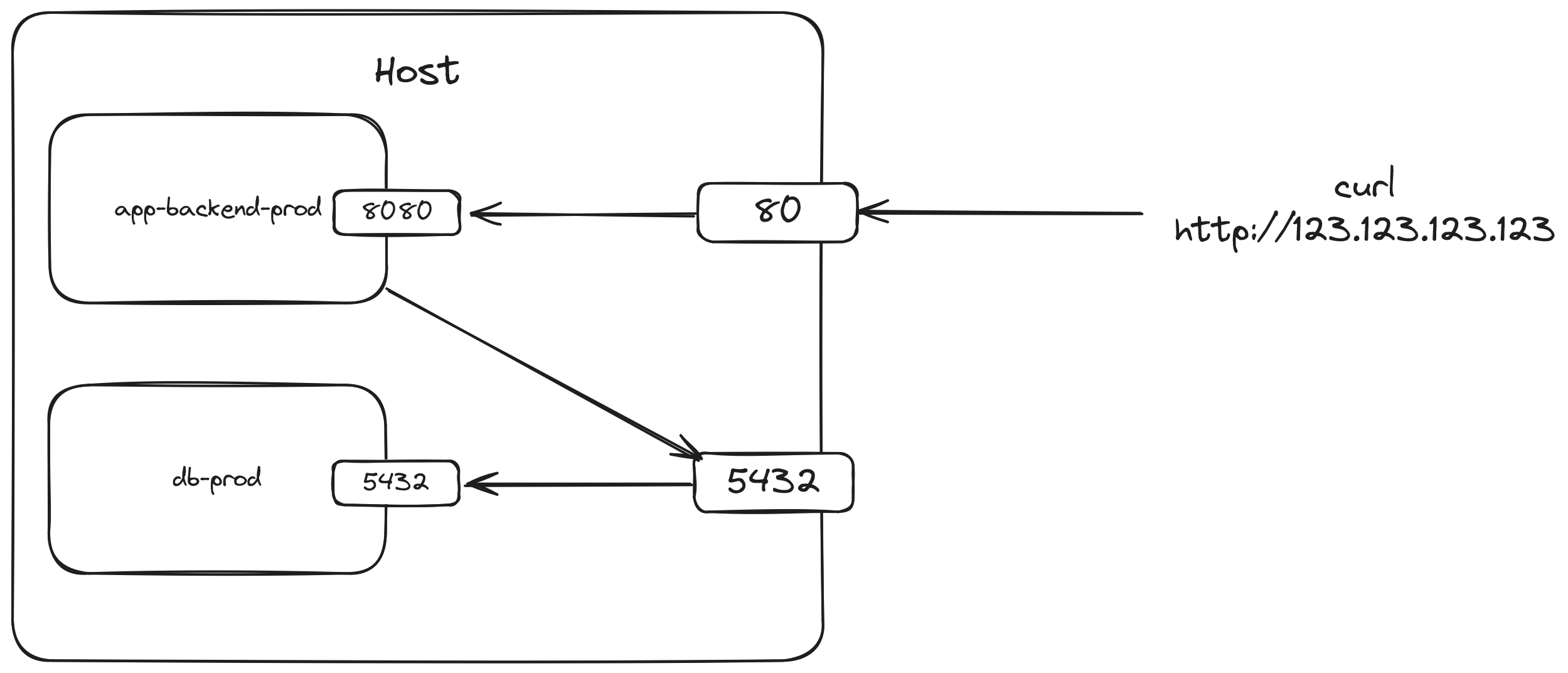

Consider the following scenario: you have an application that needs to be connected to a database and due to resource or budget constraints, both the app and the database are run on the same host using Docker.

A fairly simple setup may look like this

services:

db:

name: db-prod

image: postgres:16

environment:

POSTGRES_DB: postgres

POSTGRES_USER: postgres

POSTGRES_PASSWORD: postgres

ports:

- 5432:5432

volumes:

- db:/var/lib/postgresql/data

backend:

name: app-backend-prod

image: chevonair/app-backend:latest

env_file: .env

ports:

- 80:8080

depends_on:

- db

extra_hosts:

- host.docker.internal:host-gateway

volumes:

db:

The following setup runs a database on port 5432 of the container and it is accessible through the host through port 5432 also. Docker containers can access processes running on the host's ports through a special hostname called host.docker.internal. This means the application container can connect to the database using a connection url such as postgres://postgres:postgres@host.docker.internal:5432/postgres.

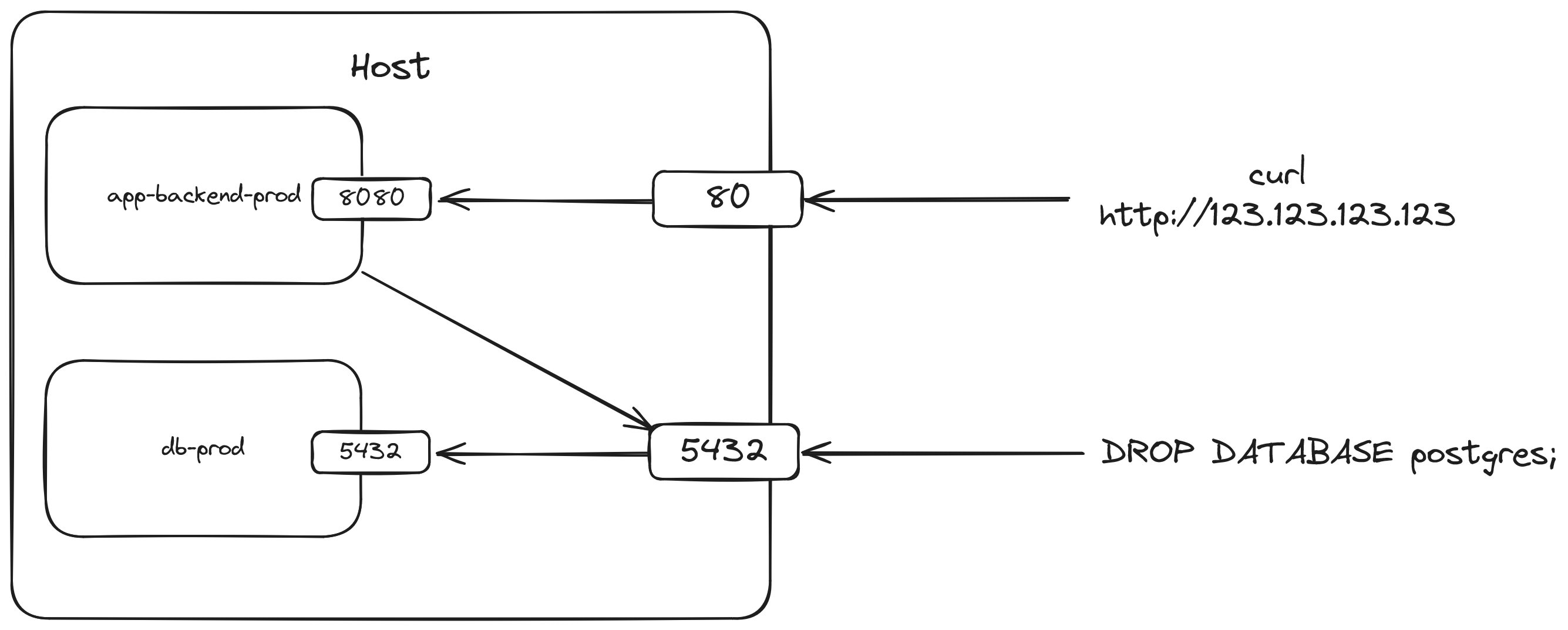

Notice that both the 80 and 5432 ports are open on the host. One thing that I intentionally omitted was that a mapping of 3000:8080 is actually 0.0.0.0:3000:8080 which means anyone on the internet can access port 80 of the machine. This may be fine if the application is truly meant to be public (except the fact that it's in http instead of https) but port 5432 is also exposed this way. This means anyone that knows the IP address of the machine can attempt to connect to port 5432! Since we used default values for the database's configuration (postgres for the database name, user, and password), it becomes very easy for anyone to get full access to the production database. A malicious actor could easily access all sensitive data on the database or even delete the database if they wanted to!

Of course, it's also bad security practice to use default values but that's a completely different issue. The sentiment is still there: anyone with a good enough internet connection from anywhere in the world can connect to the database because of the exposed port. Now, you may think that this is no issue if you've setup a firewall rule, perhaps through ufw, that denies all incoming traffic by default like this.

ufw default deny incoming

However, Docker actually bypasses any rules configured by ufw and is able to alter iptables themselves. This means even if you did block the port on ufw it can still be exposed by Docker. This is a pretty well-documented security flaw on GitHub. There are ways that can be used to prevent Docker from altering iptables itself but it's not configured by default.

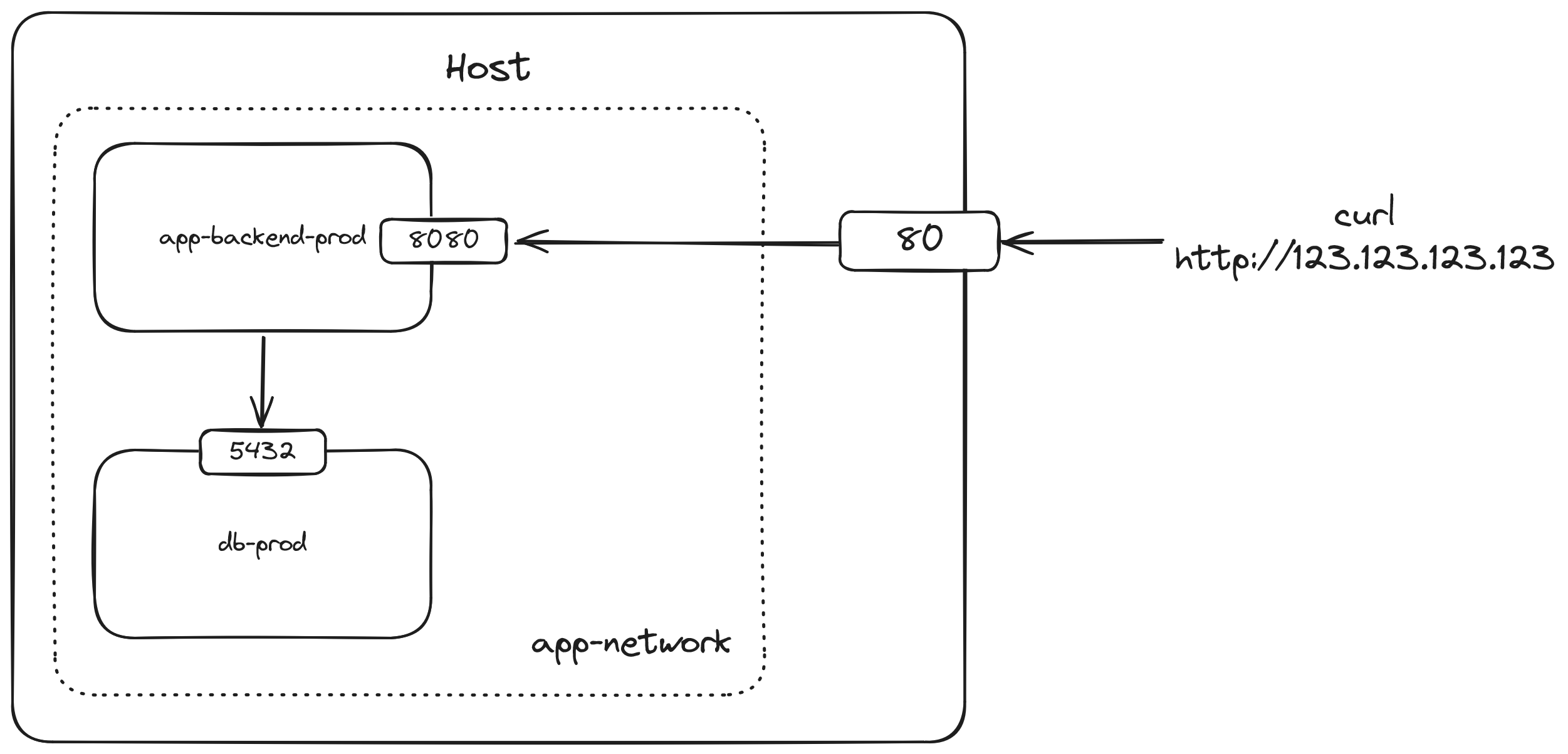

Bridging the gap

A better way to do this is to put the containers that needs to communicate with each other in the same network so you don't have to expose the ports to host at all if you don't need to. There are many network drivers available in Docker but the simplest one for our case is the bridge network. A bridge network allows containers that are connected to it to communicate with each other using their own ports. Containers in different bridge networks can't communicate with each other so they isolate containers that don't need to know about each other. You can read more about other network drivers here.

With this setup, the app container can communicate with the database container using the container's port 5432 directly without needing to expose the database to the host as this information is provided to all containers in the app-network bridge network. The host section of the database url can now reference the database container's name instead of host.docker.internal. The docker-compose.yml configuration looks like this

services:

db:

name: db-prod

image: postgres:16

environment:

POSTGRES_DB: postgres

POSTGRES_USER: postgres

POSTGRES_PASSWORD: postgres

volumes:

- db:/var/lib/postgresql/data

networks:

- app-network

backend:

name: app-backend-prod

image: chevonair/app-backend:latest

env_file: .env

ports:

- 80:8080

depends_on:

- db

networks:

- app-network

networks:

app-network:

driver: bridge

volumes:

db:

Notice that the networks directive is added to each container. It specifies what networks will these containers be connected to. We specify app-network as one of the values to say that we want these containers to connect to the app-network network. We also define a root networks directive where we defined the network configuration for app-network using the bridge driver. With this, the app can communicately safely with the database without needing to expose it to the internet.

Conclusion

Docker is a very neat tool that packages old concepts in the operating systems and networking world into a simple solution for deployments and development environments. However, that simplicity can often hide security flaws such as unintentionally exposing ports as we've demonstrated before. I hope this post not only shows how bridge networks prevent this issue but also give you a bit of insight on some networking concepts in Docker and how Docker works in general.

As always, thank you for reading and until next time!

References

- Networking | Docker Docs

- Network drivers | Docker Docs

- Bridge network driver | Docker Docs

- Explore networking features on Docker Desktop | Docker Docs

- From inside of a Docker container, how do I connect to the localhost of the machine?

- Docker bypasses ufw firewall rules · Issue #690 · docker/for-linux

- How to fix the Docker and UFW security flaw